A few weeks ago, my wife and I visited Ogaki Castle.

I walked in expecting what I have always known museums to be. Glass displays. Spotlights. Artifacts resting behind barriers that signal distance more than protection.

Then I noticed something that did not fit that pattern.

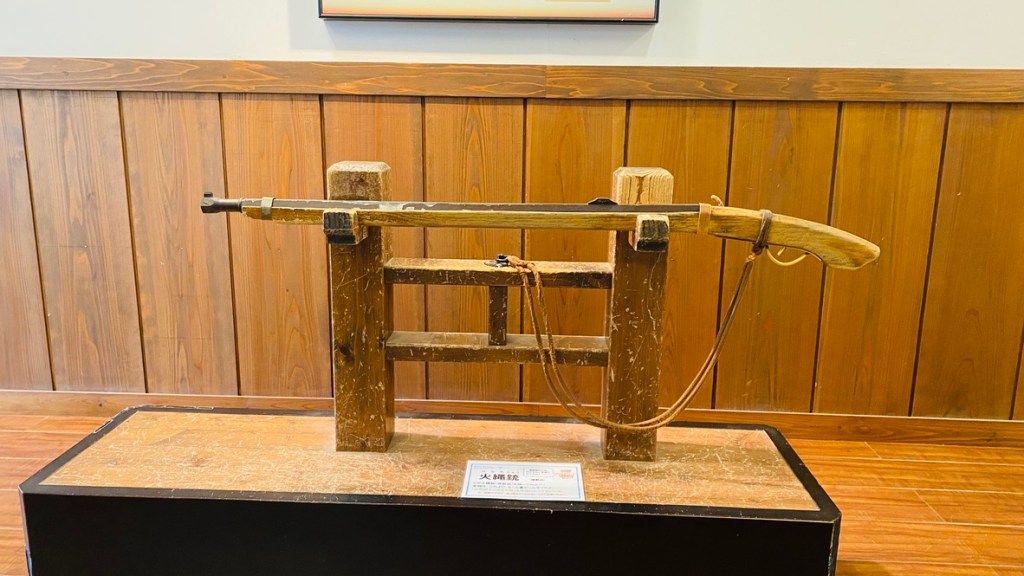

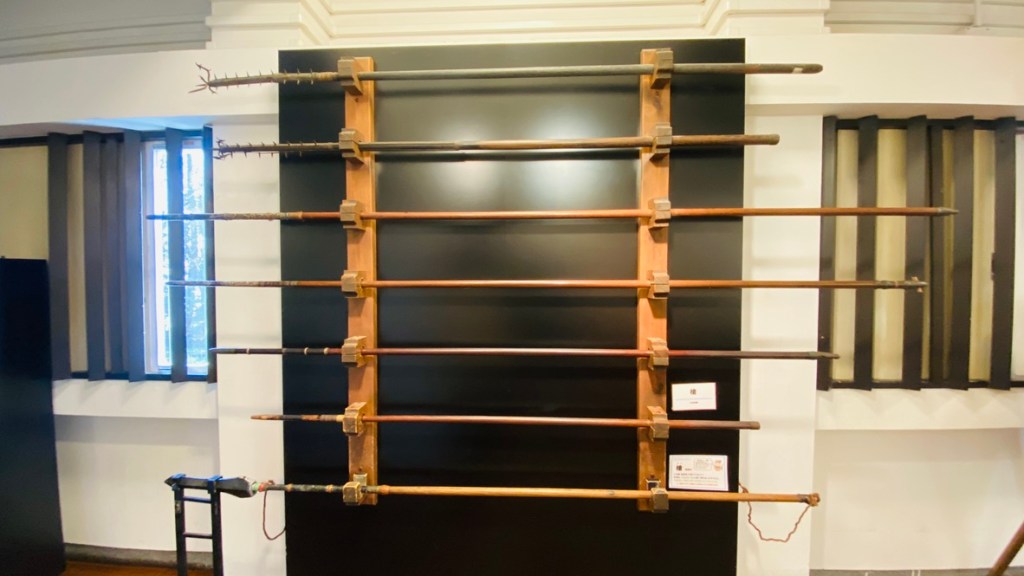

Weapons were not behind glass.

Spears. Bows. Matchlock rifles. Battlefield tools. Positioned within reach, not sealed away. No heavy casing. No visible alarms. Just objects placed in the same space as the visitor.

So I stepped closer and interacted with the exhibit.

I had seen this once before at the museum of the Battle of Sekigahara. At the time it registered as unusual, but I treated it as a one off. Ogaki Castle made it clearer. And after that, I began noticing the same approach in other museums as well.

In many European museums, the relationship to artifacts is visual. You observe from a distance. You read the description. You imagine the weight, the texture, the function.

Here, proximity changes the format. You can examine objects at the distance they were meant to exist in. In some cases, you can handle them.

That accessibility does not mean preservation is ignored. Many museums provide reinforced originals or carefully produced replicas specifically for interaction, balancing conservation with physical reference.

Standing in front of these displays, the objects present themselves differently. Construction details become easier to read. Scale becomes clearer. Wear patterns stand out. The tools appear less symbolic and more functional.

The museum space itself shifts as a result. Less like a vault. More like an environment designed for direct encounter.

Behind glass, history remains preserved.

Within reach, it occupies the same space as the present.

Leave a comment